I developed a new tension pair for introducing digital practices. Thought I’d share. Lemme know how it goes if you use it.

My planning prep for a course is to have a number of possible activities in the hopper that I can pull out and use, or make something up, or use an activity suggested by a participant. I have short canned slide decks. I have writing/chatting prompts. In class short readings. And, of course, the usual bevy of ways to get people talking to each other all designed to create an environment in which everyone can come to know. I always have general places I assume we’ll want to get to, but I think that in a post-knowledge-scarcity world, its pretty presumptuous to think that you know what a group of people you don’t know are going to need to learn before you’ve even met them.

I spend an inordinate amount of time, however, worrying myself about what the first activity for the course will be. Those first couple of moments a learner spends in a class are critical, in my view, to establish the first threads of the social contract. It sets a tone. What’s this course going to be like? What is going to be expected of me? Am I allowed to have opinions? If I walk into a class, spend thirty minutes on a slidedeck intro and goal setting, I’ve basically told everyone that they’re job in my class is to sit and listen. This is not what I want.

I tend to have have a two step process at the start of day 1 – one activity that gets people working together, right out of the gate, and one that gets them to reflect on who they are (and who other people might be) with regards to the intent of the course. This stuff is stolen and learned from dozens of awesome practitioners over the years. Thanks to all ya’ll.

First step – get people relying on each other

6 or 8 years ago i tried the most extreme version of the first intro. I walked into the class, made a brief (2min) introduction, suggested that they form groups of four to register for twitter, wordpress, the moodle course and (something else, can’t remember) and then i walked back out the door. It was a response to the consistent challenge i’d been having of people looking to me for step by step explanations. To thinking that somehow I was in the room to explain to people how to use technology. It did work. When i walked back in five minutes later everyone was up, explaining to each other what was going on and getting things done. But it’s kind of a jerk move. And it doesn’t really serve people who are not feeling safe in the classroom. So…

That… was probably taking the thing a little too far. But it does illustrate what I’m trying to get done with the intro. I want people to look to other classmates for help, for guidance, for hints. There is no such thing as cheating, there is only learning. I want engagement.

In the Digital Practices class we built things out of cardboard. We used my precious cardboard screws to build some random structures as a group. I just said “build something with the cardboard”. I was looking for a couple of different things. i wanted to see if anyone looked on the internet for instructions (they didn’t) and I wanted to get a sense of how the social dynamics would come together. It also, I hope, helped build those other social contract things like creativity, like there not being a particular thing they needed to build, independence etc… that would fold into the rest of the course.

The first activity – part two

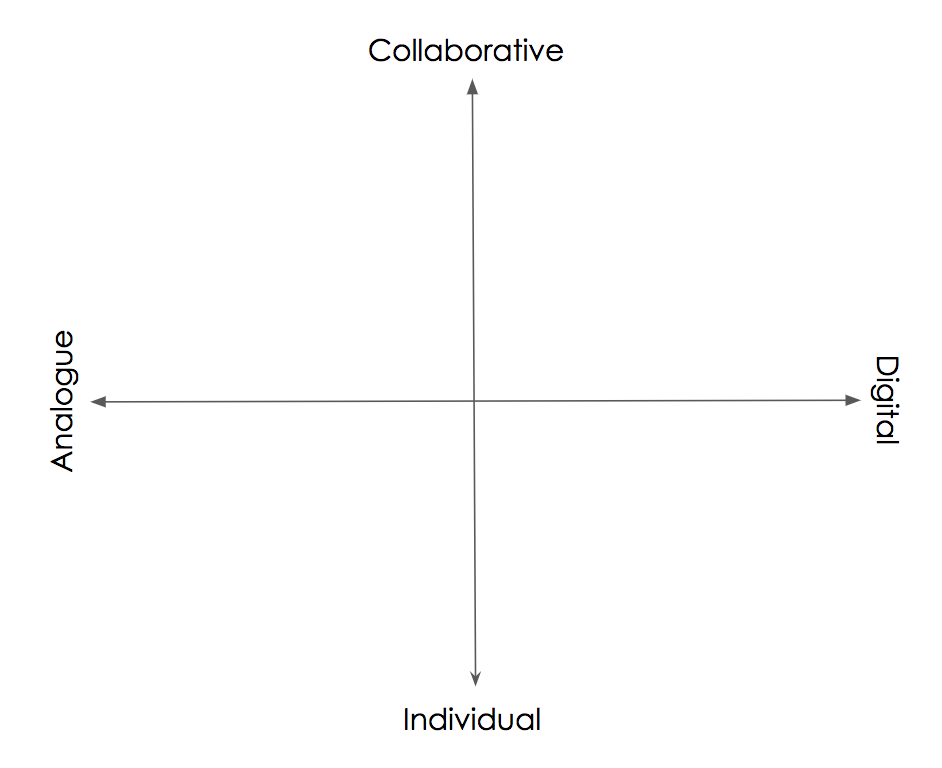

I was lucky enough to be drawing at the table with Dave White and Lawrie Phipps when the first V&R map was drawn in a little canal side bar in the UK 10 or so years ago. I love me a tension pair. I like how tension pair maps allow you to bring together two sets of concepts into one space. If you’ve never used V&R its a model that gives people a sense of where their tool use is on the digital spectrum. On one axis it goes from personal to professional (clear enough) and the other from visitor to resident. I’ll leave you to read Dave White’s blog for a more detailed sense, but a visitor dabbles (like lurking on twitter) and a resident engages (like someone who goes to twitter and replies to people on a regular basis).

It’s a useful model… but it sets the digital apart as something that either ‘is digital’ or ‘is not digital’. I was looking for something that looked at the whole of someone’s practice rather than just the digital stuff. And V&R tends to look at things from a tool based perspective, rather than from the perspective of what someone is trying to get done. I wanted us to look at ourselves from the perspectives of ALL of our practice… and see what its digital qualities might be. I wanted each participant to be able to see what each other considered to be part of the ‘professional practice’ and where they considered that practice to fit in the mapping activity.

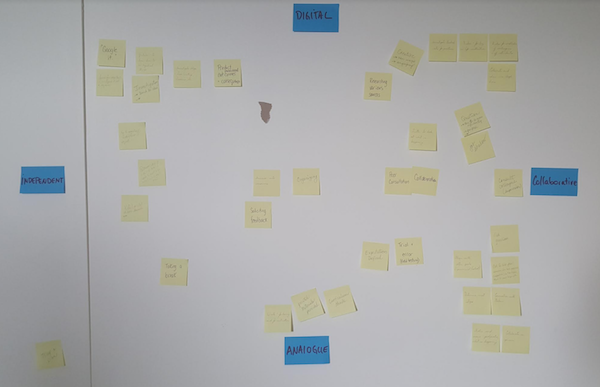

I popped four pieces of blue sticky note on the wall with the words from the pic above creating the map. Do you do your professional planning by yourself on paper? drop a sticky note with “professional planning” in the bottom left quadrant.

The nice thing about this activity is that it kept us focused on ‘what is a professional practice’ as a first point of interest and the digital quality of it as a secondary conversation. It also prompted any number of conversations between us about how digital a particular practice really is. Is email ‘really’ a digital practice? Write a letter, send it to someone, wait for a response? Not so digital. Lots of interesting discussion and the start of some goal setting.

It seemed to work. lemme know how it goes for you.