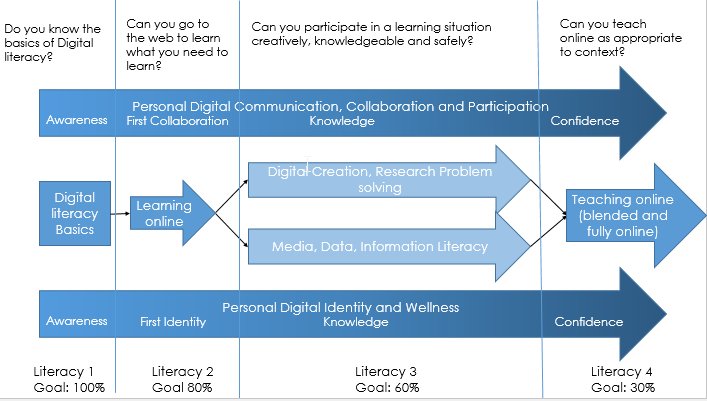

I got asked by a long time colleague if I was willing to do a post of all the things that I’ve learned in the last eight weeks about moving online. Not ’emergency teaching’ but actual lessons about people moving to teaching with the internet. I’ve worked with over 100 faculty at my own institution this past few months, taking them through a 1 week intensive course. I’ve also been in constant contact with folks from around the world both through my interviews on http://oliah.ca and in endless backchannels and side chats. Here’s what I got.

1. Moving to teaching on the internet is not a technology problem (unless you make it one)

In our course we have been treating online teaching as a conceptual problem. There are things that you can do face 2 face (like make groups quickly) that can be super difficult online. There are other things you can do online that simply don’t work face 2 face (see design your activity for the internet a little later in this list). The technology is something you will figure out through repeated use. Don’t worry about it. Just set aside enough time over successive days to use the tech repeatedly and it will come to you. Concentrate on how the internet is different. If you choose to use too many platforms or try to be too fancy, though, your technology could become a problem. Keep it simple.

2. Moving to the internet is about understanding information abundance

One of the critical pieces of conceptual work is adjusting to the idea that your students already have access to all of the precious information you were planning to give them in class. If you’ve asked a yes or no question, or you have asked a ‘complicated’ question that has a fairly recognized answer, your students are going to google the answer to it. As they should. Those of us with access to the internet (through literacy, technological and financial means) can reach out for any piece of information we need by simply searching for it. Our learning experiences need to reflect that.

3. Complicated vs. complex concepts on the internet

I’ve found the distinction between complicated and complex concepts a good way of keeping track of what I’m asking students to do. A complicated concept is one that responds to a step by step answer. Thought of another way, it’s an answer you could copy and paste. Those answers only work in that bubble of artificial scarcity that are our f2f classes. If you’re looking to evaluate a student’s work online, add some complexity. Something that personalizes the issue to the student. Something that brings their perspective to bear. I’m not saying we can’t teach basic concepts that learners need to remember, just make them part of other things that include complexity if you want to do an assessment.

4. Learning to evaluate good/bad information on the internet is a core skill in any field.

One of the big objections to embracing that giant, complex abundance of information is that students wont know what is good information and what is bad information. This is true. But learning how to find, evaluate and combine information in any field is a critical skill right now. We can’t protect them from the internet. They need to learn how to deal with it.

Our students are going to need more than information to address the challenges they’re facing. They need to be innovators, problem solvers, and strategic thinkers. You may not have had time to include those kinds of activities in your classes before. But now that your students have all of the information, think about how you can address some of these higher order thinking skills.

5. Pedagogies of care (for students and teachers)

We’ve always needed to take time to care for ourselves and our students. One of the challenges of moving online is that we need to consciously think about how we are to ‘care’ for our students. A smile in the classroom can mean a great deal to our students. How are you going to incorporate that caring in your messages? In your videos? In how you design assignments? At the same time, our face 2 face schools also wrap some sanity around how much work we do as teachers. How can we balance the care that we are giving to our students and the care we are giving to ourselves? Imagine what you do the first five minutes of class (smiles, check-ins) and think about ways to do that online.

6. Think of ‘content’ as ‘teacher presence’

One of the concepts we’ve found useful is in thinking about everything a teacher does as teacher presence. In a f2f classroom the work that we do, dropping a comment in a discussion group or explaining a complex concept are conceptually different from a textbook or an assignment. Online all of this stuff combines into your ‘presence’. There is usually a direct relationship between your perceived presence and student engagement. I say perceived presence, because you need to let students know you’re there… simply reading their comments in a discussion forum and not saying anything doesn’t let students know that you’re present. You need to ‘be present’ the same way you need to ‘pay attention’. It’s an action.

You can easily write one post responding to all the posts on a given subject, highlighting themes and correcting misconceptions. Less duplication for you, and it still shows students that you’re involved.

7. Keep it simple

This is the first of the three messages from http://k12.oliah.ca about how to move to working online. I had a great discussion with one of the science faculty members in our course this week and he was saying that he realized he had to stop ‘covering the content’. He’s always kind of suspected that he was going over too many concepts in his class and that students weren’t getting them. In his move online, he’s focusing on far fewer concepts and digging much deeper. Keep it simple. Focus on the stuff that’s important.

8. Keep it equitable and accessible

This is part access, part care and all about thinking about your context. The accessibility issues that your students have are not going away because they are working from home. Using UDL approaches in your learning and working with student support staff is critical.

Online learning increases the impact of economic disparity on the classroom. If you don’t have a dedicated computer in your house, you are going to struggle to participate in a synchronous activity. You are going to struggle multitasking on a phone or tablet. Many students would go TO SCHOOL, or the library, or McDonald’s to get access to consistent wifi. They may not be able to do this. Think about different ways you can design your assignments to allow for students to complete them in multiple ways. This video does an excellent job of talking through this concept.

9. Keep it engaging

One of the biggest concerns I’ve heard from people moving online is that they struggle to get students to do the work face 2 face, how are they going to get students to do the work online. Part of helping students be engaged is to create the scaffolding they need to understand HOW to be ready to do the work. If you’re assigning readings before a class, give them a 200 word reflection to hand in the day before. Scaffolding doesn’t mean you oversimplify the material, it means you structure the workload, particularly at first, and then maybe reduce that scaffolding as learners get comfortable. If you’re moving away from Multiple choice questions because they don’t work online (and they mostly don’t) you’ll need to apply this scaffolding to let them know what success looks like.

Also. You need to be interesting. If you’ve recorded a super long video to send to students, force yourself to watch it first. When you get bored and want to turn it off… cut your video and send that. 🙂 Imagine yourself as a student. Really work through what the student experience is going to be.

10. Design activities for what the web can do for you.

This concept seems to be helpful to people thinking about the advantages of teaching online. If you’re going to have an essay or a project or any kind of long term work with students, think of those projects as an iterative process. If you were doing this face 2 face, you might have them submit something halfway through the term. You might even get them to journal in a workbook that they hand in to you and that you hand back. It’s an organizational nightmare. Online you can create any number of spaces where learners can check in and post their progress. The web is very good at keeping track of student work for you. It also makes it very easy for students to share with each other.

For this to work, you can’t think of grading EVERYTHING. Setting up discussion for students and having them submit ‘their five favourite posts’ can be a great way to keep discussion open and also introduce curation.

11. Gather resources together… together

Please don’t try and do this alone. YOU ARE NOT THE ONLY ONE TRYING TO DO THIS. IT IS NOT A COMPETITION. Don’t try to create all your resources alone. Don’t try and learn alone. Don’t try to find your resources alone. Make a team. At your school or with others. Here are a few lists of resources.

List of resources about teaching online

List of virtual labs

List of review of online tools for teaching (The Open Page)

Online Learning in a Hurry

#OTT20 ONLINE TEACHING TUESDAYS (Drop in discussion)

There are tons of Open Education Resources (OER) out there you can use. It takes a while. And some deep searching… searching with a team will make it much faster.

12. Last note: If you’re helping someone else

People don’t need to understand the technical language of design. They just need to understand why they need to do what you’re talking to them about.