What follows is an introduction I wrote for an upcoming edited book on Rhizomatic Learning. It’s not really an introduction, or a preface or a prologue. Frankly I’m not sure what it is. It is certainly a story I’ve been wanting to tell. It’s also too long for a blog post, for which I apologize.

Citation: Grandal Ayala, M. y Peña Acuña, B. (eds.) (2018) Rhizomatic Learning. Madrid: ACCI.

It’s a funny word, rhizome. It is a stem of a plant that sends out shoots and roots from its nodes. Many of the plants in our gardens that we call weeds actually spread by this method. You end up with a ball of roots, random shoots popping up out of the ground here and there, and a plant that you can’t really control. It’s this clever quality, one imagines, that led to it being used by two french philosophers, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari in their somewhat peculiar book, A Thousand Plateaus.

I have developed courses, taught MOOCs and had many, many discussions teasing out the story of the rhizome for learning. I will avoid the temptation, however, to try and dive down the rabbit hole to explain the historical context of D&Gs philosophy, or the nuance of their somewhat curious masterpiece, A Thousand Plateaus. I am not the person to make this attempt. I came across the rhizome as its roots were spreading through my network; I came as an educator looking for answers to some of the questions that I had in the classroom. Many of you are likely coming to this book with a deeper understanding of the place of D&G in philosophy, and a more literal, perhaps, interpretation of the work of these too brave philosophers. This prologue may be frustrating for you, as my intention is not (nor has it ever been) to be true to the work that has gone before me. I have stolen from D&G, magpie-like, to help me build a story for my own learning.

I have also avoided defining rhizomatic learning. When we define something, particularly in writing, we necessarily exclude some of the nuance of the meaning. We leave out the chance that the definition can get better. We leave out another’s perspective. What I want to do is tell the story of rhizomatic learning from my perspective, my personal journey. To talk a little about what the concept has done for my teaching, my learning and my understanding of the world.

So I apologize for leaving you without a definition or a clear theory of rhizomatic learning, however useful these things could be. Theories, like definitions, help create a shared common language. As we reify language into chunks it creates a shorthand that allows us to communicate faster and more effectively. It also means that we are less likely to misunderstand each other as we have a shared ‘meaning’ for the words that we are using. I am not able to provide this certainty. But with this loss of certainty of meaning there is freedom. Feel free to take this into your own hands and draw the conclusions that work for you.

I was first introduced to the word ‘rhizome’ in 2004[note: by Bonnie Stewart]. I was approaching that 4-5 year mark as an educator and had been trying to understand why we shape the learning experience the way that we do. I was starting to accumulate a set of approaches that seemed to match my style. I had a reasonable expectation, walking into a class, that it probably wasn’t going to be a disaster. And I was reading. And that reading was starting to bother me. There was a discrepancy between some (many) of the things that I was reading and what seemed to be working in my class. I was clearly not doing what other people thought I was supposed to be doing.

Teaching in a graded environment is a true position of power. You get to decide, as a teacher, what someone needs to know and whether or not that person knows it. You get to set the measures of success. I had the same sense of imposter syndrome that many of us do in that situation. Who am I to be in a position to decide what someone else should know? What gave me the right to exercise the power that I had over my students? Sure, my grading matched my rubric, but I had just made up the rubric, how was that fair? Was I ready to accept the implications of failing a student?

All the questions I had, though, fell under the category of THE question of education. What does it mean to learn? I could see it in students in my classes, and had experienced it myself, but I was looking for a way to understand it… a definition of it that I could use. I was looking for a touchstone that I could use to justify the work I was doing.

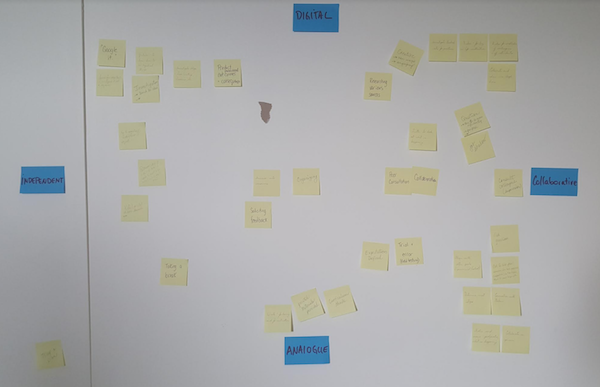

I had just started experimenting with different technology supported learning methods at the same time. The use of those technologies seemed to have a fairly significant impact on what it was possible to do in my classrooms. The work that my students were doing suddenly became more diverse and more individualized, and, at the same time, I had lost some control over the teaching process. Had the learning changed? What impact does the technology that we use (think of technology broadly here, to include things like pens and books) have on what it means to learn? Was it better or worse that my students were handing me assignments that didn’t match what I had assigned? How could I assess them fairly?

The research I was reading indicated that students were ‘most successful’ when they had a clear expectation of what success could look like. Clear goals for each learning event combined with a perfectly structured class was a clear indication of someone who took the profession of education seriously. This is what it meant to be expert teacher. I struggled to match this perspective on expertise to the new experiences that were happening in my classroom. Telling someone what success looks like seemed like a poor way of empowering students to take control of their learning.

The textbooks that were a part of the day to day of my classroom supported this very structured, linear approach to what learning should be. It set out assignments that were connected to the content. There were answers to those assignments. Clear answers. Some of those answers were hidden in the back of the book and some were hidden in the magic book that was at my desk – The Teacher’s Copy. My job seemed to be to hide the answers to questions from my students and then work with students until they could guess them. The Internet was starting to make that a difficult game to win.

But all the time I was writing lesson plans (or feeling bad because I wasn’t writing them) I was thinking about the future students I would encounter. My own academic path and that of my peers had already shown me that learners are not an homogenous group; did the literature really expect me to accept that a one size fits all approach would be successful? How could I know what a student needed to know before I met them? Was there some canon of knowledge that I could simply go to and pick the right topics off a shelf that would be applicable to everyone? How could I decide, ahead of time, what success was going to look like for a student?

I was becoming more suspicious of that textbook. How much had the technology of print (that is, the ability to use a press to rapidly add words to a page) impacted what we thought learning could be? How much and how many of our practices were shaped because of the practical realities required for the writing, editing, printing, binding and shipping of books from one place to another? How many practices, by extension, were impacted by the process of knowledge access that happens in a typical school? In a print world, a classroom is limited by what I have in my head as a teacher, what are in the books I thought to order ahead of time, the books in my school and, if I’m teaching well, in the heads of my students.

This leaves you with little choice other than to plan ahead of time. If I need a book to be in my classroom on day 1, someone needs to chop down a tree, mash it into paper, throw a pile of ink on it and send it to me in a truck. All these things take time. I need to be completely prepared with ‘content’ before the classroom starts. I have to create the uncertainty in the classroom. I, as a teacher, control the uncertainty.

The Internet has changed that. Right here and now, with the ability to search I have access to an almost limitless amount of information. It may not be the best information, it may be controlled in ways that I don’t understand, but I can access it. And, furthermore, if the information is available everywhere, what does that mean to the content I use in my class?

This is when I came across the concept of the rhizome. It moved differently than the static models that I had been working with. It felt like a radical step away from the kinds of conversations I was having. It refused to be defined in any way that made sense to me. The thought suddenly occurred to me that the reason I’d been struggling to find a definition for learning was that it wasn’t the sort of thing that could be defined. I needed a story for what learning meant to me, and I had found it in a deeply troubling book. In the story of a plant that chooses its own paths, that is resilient and difficult to control. I have spent the last 13 years thinking about that story. How has technology impacted what we think learning can be? What is that learning?

The story starts in the law courts of the late Roman Republic. Two fantastically talented, obscenely vain men, who shared one talent that was vital for success in the last century BCE. They could talk. They could convince, cajole, overwhelm and persuade people through the power of their voices. They are Marcus Tullius Cicero and Gaius Julius Caesar.

Cicero was a ‘new man’ from a small town outside of the city of Rome. His family was comfortable but not connected. New men very rarely made a splash in the complex web of Roman Republic politics. This one did though. He made an entire career out of his ability to use his voice first in the law courts and eventually in the senate house. He wrote books about how to give a speech in public. They focused on one thing – being able to go to the hearts of people. To bring them on-side. Once you’d accomplished this, there was no fact or figure that could work against you.

Caesar on the other hand was a scion of one of the oldest families in Rome – the Julian clan. His ancestry was traced back all the way to the founding families of the city and, according to family lore, he was the descendant of the Goddess Venus herself. While privileged in a way that Cicero was certainly not, he had to navigate the waters of conflicting allegiances, family marriages and Roman political alliances to make his way to notoriety. His constant companion was the ability to convince powerful figures to trust him as a politician, convince his soldiers to follow him as a general, to inspire the people of Rome to love him as their leader.

Another thing both of them had in common is that they studied under the same teacher; Apollonius of Rhodes. He ran a school of rhetoric that was widely reputed to be the best available in the Mediterranean. Students came from all over to become the best public speaker they could be. It was no casual journey to get to see the famous rhetorician. Travel at the time period was difficult and dangerous. Caesar was captured and ransomed by pirates on his journey to the island. While I would argue that mentorship from a master is going to rival if not beat any kind of learning that you are going to attempt – that privilege, clearly, is not easily won.

In 70BC, if you wanted to learn at the feet of the masters you had to be committed.

The learning Caesar and Cicero were trying to acquire was complex. They wanted to sway, to galvanize the hearts and minds of their listeners, to make them see things through their eyes. There’s no record of what Caesar learned in his time on the island, but for Cicero it was patience. He would throw too much of himself into his oratory, tire himself out, use up his voice. Apollonius taught him to be patient, to work his way towards a conclusion. Could he have learned this from a book? Would he have had the self-reflection to see where his flaws as a rhetorician laid and found a path to expertise. It’s possible. But these learning journeys are individual, different for each of us and impossible to prescribe for all. Or even for two. Learning of this type cannot scale. It is the kind of learning that can be given from one (or many) to one.

The second part of this story takes place in the year 1270. We are at the University of Paris reading an advertisement for another university on the other side of France in Toulouse. The flyer reads,

“Those who wish to scrutinize the bosom of nature to the inmost can hear the books of Aristotle which were forbidden at Paris.”

You can see that the role of the student in the learning process at a university in 1270 is to ‘hear’ the words of Aristotle. We lost poor Aristotle about 1500 years before the University of Toulouse existed, so we’re not only listening as a learning process, we’re also listening to someone who is no longer with us. We are looking at a perspective of the world that was thought and worked through a long time ago. Content that, as Plato suggested in the Phaedrus, is dead. It cannot be interacted with.

The predominant teaching method at this time is catechetical. It’s call and repeat. I might read a passage of Aristotle and then have the students repeat it to commit it to memory. And this made sense, given what was available to them at the time. One single book of Aristotle’s Physics (the book that was banned at Paris for making a variety of suggestions about the natural world that didn’t agree with the church’s perspectives on science) might be made from the skins of 200 animals. In a world before the printing press – in a world before paper – where we rarely allow students to touch books.

This means that a university like Paris has control over access to knowledge in a way that far supersedes anything you could do today. Certainly the ability to write down and record what Aristotle said is powerful, but the limitations of the technology have a profound impact on what we can do from a learning perspective. Certainly there are more people involved in the learning than there were in our Roman example, the advent of universities certainly means that more people can ‘learn’, but it means that the experience of learning is profoundly different.

When we are dealing with a dead argument that is delivered in the catechetical approach the tendency is to work towards remembering the argument rather than learning from it. The Monastic approach is to ‘lectura’ literally “to read” and hence we have lecture, an elevated position at the front of a room from which the learners listen to the reading from the lecturer. This was a far cry from the relationship between the master and learner on the Isle of Rhodes. Success is to repeat. Not much sense arguing with Aristotle about it, as he is not able to reply. It also means that the person reading the book at the front of the class that you are ‘hearing’ might not understand Aristotle the same way that Aristotle did. They may not understand it at all. If someone’s job is to read any number of books to you there is a much, much better chance that that person is not an expert on the subject that you are listening to. Your questions as a student, then, are more likely to be of the ‘What did Aristotle say?’ rather than ‘What did Aristotle mean?’

[NOTE: There is a giant piece in here that i didn’t get finished for the release of the book about how the Scholastics and the Humanists interact in all of this. Broadly speaking, the scholastics were certainly more interactive in their teaching style, but their epistemic foundation was still iconic Christian texts. A scholastic found things that seemed to contradict in extant religious texts, and then argued until they figured out why they didn’t exactly contradict. I can’t help but see what i think of as ‘fake’ project based learning in this. We want you to collaboratively explore your way to the solution that we have already decided you will find.

The humanists were a whole other bag of potatoes. I’m hoping to write a piece on them eventually, suffice it to say that the black death (circa 1350) left some people believing that there were other sources of knowledge than the christian texts. Also, for instance, artists were dissecting human cadavers at this point and discovering that Galen was wrong as well. The first glimpses that ‘knowing’ might be more than ‘knowing what came before’. see n. renaissance. ENDNOTE]

Lets jump forward a little more than 400 years to the little country of Switzerland, nestled in the middle of early modern Europe. The year is 1800 and Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, having just failed as headmaster of an innovative school in the capital city, has a new dream. He wants to train an entire country how to read. Think about that. This is before there is a public school system. There are no teacher education programs. He had to come up with an approach that would allow regular people, with limited literacy, to teach others how to read, write and do basic arithmetic.

His solution was the textbook. We have moved on from having to slay a field full of animals in order to create a single book. We are now making books out of paper. And, even better, it doesn’t require a monk to spend half a year painstakingly writing out the book one word at a time. We have a printing press. We can decide what to put in a book, set it up on the press, and make 10000 identical copies.

At the same time, we are moving our student another step away from the content. We’re also requiring even less from the person who is facilitating the learning process. In Pestalozzi’s own words from “How Gertrude Teaches Her Children,”

“I assert definitely that a school-book is only good when an uninstructed schoolmaster can use it at need, [almost as well as an instructed and talented one].”

We’re a long way from our trip to see Apollonius at Rhodes who was evaluating the needs of every student in the terms of their journey. When we standardize not only the content but also the teaching, we’re increasingly forcing each student down the same road. We’re trading freedom for scale. Certainly the kind of one on one learning that was happening in Rome is still happening at this time, but learning, the system of learning, has become something different.

Pestalozzi’s dream is the one that most of us share. We want to be able to have a literate population. We don’t, most of us, want to limit literacy to a select group of people who won the financial birth lottery that gave them the resources and the free time to go about finding a mentor who can teach them as an individual. And we’ve expanded what we want that literacy to be. We want students to understand the world around them. How then, can we achieve the kind of student directed learning that allows Cicero to be the best that he can be and still allow everyone to do it? The experience Cicero had on the island is important, yes, but not as important as the decision to go there in the first place. It is, in a sense, the decision to learn that we are trying to teach. We are trying to enforce independence.

The influence of text, then, is profound. It allows us to scale the learning process, to allow more people to participate. In order for this to happen, however, we need to standardize first the content (in the case of the book) and then the process, in the case of the textbook. We’re creating paths in the smooth space of possibility. Because you have to kill a pile of cows. Because you have to arrange a pile of metal letters on a press. Because you have to plan months or years in advance of the learning process to assure that the content arrives, it creates a pattern of what learning is going to look like.

Those paths were a necessity of the technology that we had. They allowed Pestalozzi to try to teach a whole country to read. They allowed a professor from to stand up in front of a number of students and read the words of someone long dead. I think that we started to believe that those paths in the sand WERE learning. The goal was not for a learner to become something that they might want to become. The goal of learning in a textbook world was for the learner to become a follower of paths.

I am not interested in training a world of path followers. I know that anyone who is only going to learn when I’m watching them is not learning very often. They are limited by what I know, yes, but they are also limited by their translation of what they think I want them to know. This is a poor preparation for a life of learning. Or, to put it in more D&G friendly terms, I am looking to equip a nomad who can wander across a smooth uncertain space. I am looking to help support path makers. I can see the need for striation, for tracks, given the earlier technologies from our story, but I think the internet changes that. For good and for ill.

I used to think that what it meant to learn actually changed along with the technology. It seemed a dramatic thing to claim, but I now see that it takes away from the story. The real story here is that as we’ve needed more and more people to be able to read and write, our conceptions of what it means to be educated have changed along with it. The journey, the coming to know of the learner, remains the same.

In a catechetical classroom, we reward obedience. Obedience to the process of call and repeat and a strict adherence to the word that has been said. In a textbook classroom, we reward getting through the process. Through the path. If you follow the trail that we have set for you, and acknowledge the sign posts, you have succeeded. The passivity of the learner in our education system can be seen, at least partially, as a result of the technologies we were forced to use to scale learning.

And yet, under all this, is the learner. The learner is still on their own journey, even if they are being forced onto a striated path. They are coming to the structured event with a different background, different habits, different aptitudes and desires. However much they’ve taken a copy of what you are trying to imprint, that copy is never going to be exact. They are still gravitating to the things that make sense to them, adding those things to what they know. They are still building their own map.

I try to keep this story in mind when I try to understand what the Internet can do to my learning journey. I use it to interrogate my actions. It is the first time where the learning event can regularly contain something not planned or prepared for by the teacher, and not brought in advance by the student. It could, possibly, allow the student to allow the underground journey, that self-directed journey, to be reflected in the actual classroom.

I’ve come to believe that under that layer of technology rhizomatic learning was always happening. We can see pieces of it in the structures of our own knowledge. Follow the citations in an academic article back to their ‘source’ and you’ll find a rhizomatic web of knowing. It is self-supporting and contradictory. Always uncertain. If learning is this personal map making journey, how can we use the technology we now have to support this in our classrooms?

My job as a teacher is to create smooth space. To create an uncertain space where students have a chance to be ready to create their own map. To build an ecology within which students can grow, wander, break off and reconnect. A place where they can access the voices of the past and present and use them to learn. If my students can learn when they are uncertain, they’ll be prepared to answer questions that I cannot. And, even better, ask questions that I might not think to ask.

One of the editors of this book calls A Thousand Plateaus a walking book. It’s a book that you carry around with you with the intention of reading it, but it tends to just come with you in your bag. It requires a certain frame of mind to dig into it, a frame of mind that doesn’t occur just every day. It surprises you. It comes upon you. You need to have the book ready for when those moments occur. It is, in a sense, a good story for learning itself.