In honour of the release of Martin Weller’s book Metaphors of Edtech, I thought I’d address one of the issues that keeps coming up in my classes that I’m teaching this term. The difference between an educational concept being ‘true’ and something that has explanatory power.

In the introduction to the book Martin suggests that the research provides two key insights about metaphors…

- They are fundamental in shaping our interactions with the world

- They can be used to understand a new domain

His book is a super interesting journey through the various ways we have used things in our world to try and shed light on the complex uncertain world of learning and its accompanying systems.

I had his book in mind when I came across this tweet circulating in my feed this morning.

I started responding to the question on Twitter (potentially rhetorical, but I’m going to take it as if it wasn’t) “why in the heck does this still happen?” and decided that it was more of a blogpost.

Myths

I understand the word Myth to have originally meant something like ‘the way we explain things’. The word descends to us from the word Greek word Mythos, with a meaning that, originally, doesn’t have the sense of ‘not true’ in it. Rather, as Brzeziński suggests, “Myths have been created to give answer to the most basic questions concerning human existence.” We have our rationalist friends from the late middle ages to thank for the bait and switch in the meaning. Now myth means something like ‘things that aren’t true.’

I think of myth as a way we confront uncertainty.

Learning styles as myth

This is a hot topic in my classroom. I’m not a huge Learning Styles guy because I find that once people find a box to jump in, they don’t like to explore other boxes. I’ve heard too many students/faculty say “i’m an auditory learner” and refuse to watch the video. I know the concept of learning styles is being taught on my campus. The education students that I teach are VERY familiar with the concept and most of them have a clear idea of what their own learning style is supposed to be, regardless of whether they believe in it or not.

In their oft cited 2010 article Reiner and Willingham suggest that learning styles do not ‘lead to better learning’. As is so often the case in this kind of argument, the idea of what ‘better learning’ might be is taken for granted. They did their research in ‘controlled conditions’ and discovered that ‘learning is not improved’. There is a hint, though, where they say “These preferences are not “better” or “faster”, according to learning-styles proponents, but merely “styles.” In other words, just as our social selves have personalities, so do our memories.” (2010) Willingham, certainly, is a big memory guy. (Willingham, 2019).

So. If I’m to read between the lines here, Science has proved that using ‘learning styles’ doesn’t improve memory retention in students. This has very little impact on my teaching. I don’t test my students memory in my classes.

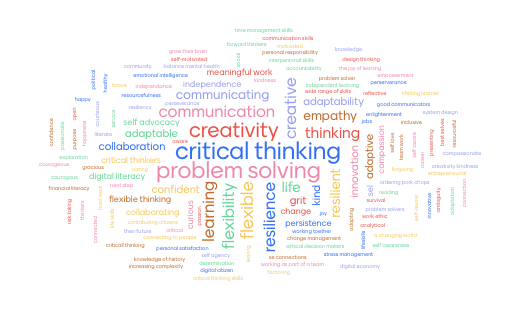

The authors do agree that learning styles advocates are right that all our students are different. That’s good. But what could it do? What if we don’t ‘believe’ in learning styles but are conscious of approaches that different students hate?

Let’s talk about math

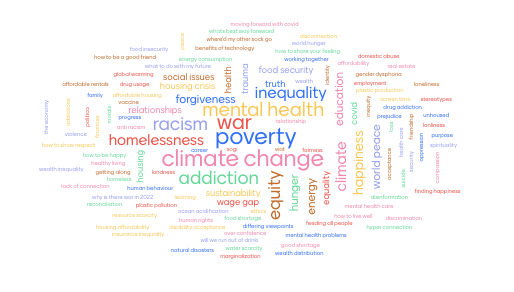

Every time I talk about uncertainty in education someone brings up doctors or math. “I wouldn’t want my doctor to learn that way (sorry. they do)” or they say “2+2 is 4, you just need to shut up and learn the math”.

Two weeks ago I was ‘helping’ my 14 year old with her grade 9 math. By ‘helping’ I mean she was explaining it to me. I relearned grade 9 math two years ago to help my other child who had fallen behind at the start of the pandemic, and promptly forgot it all again. What I noticed this time was that the math she was learning was the same math no one in my PhD program last summer could remember how to do. I mean. There might have been one person, but that person was not putting their hand up.

The topic of ‘how we felt about math’ became a conversation in several of the groups that we were in. Those who felt they ‘weren’t good at math’ were struck by a huge sense of anxiety trying to relearn the math. They had ‘learned’ that math, maybe in grade 9. They passed it. They proved at one point in time that they had it in their memory. But they didn’t consider themselves someone who ‘liked math’ or were ‘good at math’.

If a ‘learning style’ helped a student feel better about math, would that make it worthwhile? Let’s say that it had no impact on their ‘memory’ of math concepts, but they remembered math class with a sense of fondness… would that make learning styles an approach we should consider?

Does it even need to be ‘an approach’? Can we posit the idea that working with student preference leads them to be less frustrated about the work they are being forced to do? Maybe. But you’re never going to be able to ‘science’ that one in the same way. (don’t say we could do a survey)

Confronting uncertainty

Testing memory, as it can be done in ‘controlled conditions’, is one way we can ‘shape the interactions in our world’ and ‘understand a new domain’. It is a way to affix a number to the learning process. It allows us to clamp down on the uncertainty of this crazy learning thing we do and give it some clarity. It’s ‘evidence-based’. When we believe that memory is what we’re trying to do in our schools, we interact with our students differently and we understand success as a high grade on a test.

Same with learning-styles. It’s a way of trying to talk about something that we see in our classrooms. All our kids are different. They seem to learn things in different ways. Different approaches seem to be preferable to different kids. Let’s put a name on it and build some categories so we can teach people to teach to specific learning styles.

People remembering things is helpful. Paying attention to how people prefer to learn is probably a good idea. They are different ways of talking about what we call ‘learning’.

The other myths in the tweet above ‘people remember 10% of what they read’ and ‘the factory model of education’ are similar. They have explanatory power. They allow us to talk about how reading something is not ‘remembering’ something. They allow us to talk about how our schools are shaped to train people in certain ways eerily similar to factories. Are they ‘true’?

Shrug.

I think our desire to move passed simply explaining something ‘reading isn’t perfect’ to giving it a ‘model’ or a ‘truth’ is the original sin. We are trying to ‘truthify’ something that often doesn’t respond to true and false statements (though, obviously, some do). And then we follow along behind it and ‘research it’ and discover that it isn’t ‘true’.

Not everything has to be true. If learning styles are a myth, then they do explain something to me. They remind me that my student are different and that I need to pay attention to their preferences.

Even if those preferences aren’t about the math they end up remembering.

The value of metaphor

The nice thing about metaphor, is that it allows us to talk about something without troubling ourselves about the metaphor perfectly describes the world. It’s a way of making meaning by sharing how we feel about something else. It’s a different way of confronting that uncertainty. You don’t need to go find a lab and prove it isn’t true.

If I said that learning is a weed because you can’t really control what someone learns, you could nod, and think about a weed in your garden. It might connect with something else you’ve been thinking and it might not. But if by some strange happenstance you’ve made it this far down in the post, you might now have some image of a weed… and be thinking about learning.

Martin’s book

Martin’s book is a super-cool journey through the metaphors that people have used in edtech. It’s really interesting to see the different ways people have tried to tell stories about the uncertainty they’ve been confronted with.

His writing style is as good as ever. It’s a book I’m going to continue to go and drop into.

- Paper book is on sale, September 30th http://www.ubcpress.ca/metaphors-of-ed-tech for $24.99.

- Available now to read online https://read.aupress.ca/projects/metaphors-of-ed-tech

references

Brzeziński, D. (2015). The Notion of Myth in History, Ethnology and Phenomenology of Religion. Teologia i Człowiek, 32(4), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.12775/TiCz.2015.047

RIENER, C., & WILLINGHAM, D. (2010). THE MYTH OF LEARNING STYLES. Change, 42(5), 32–35. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25742629

Weller, M. (2022). Metaphors of Ed Tech. Athabasca University Press. https://read.aupress.ca/projects/metaphors-of-ed-tech

Willingham, D. T. (2019). The Digital Expansion of the Mind Gone Wrong in Education. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 8(1), 20–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2018.12.001