As I’ve mentioned various times on this blog, I have had the good fortune of working with about 70 Co-op students throughout the pandemic. They were students who would mostly have gone out to their engineering or kinesiology placements, but could not due to the pandemic. They’ve been wonderful to work with. The students I’ve worked with in the past had mostly self-selected into the work that we were doing. These students had not. They were doing their best (like so many of us) to make the best of a Covid situation. I learned a lot from them…

One of the things we’ve worked on extensively… is about what it means to be ‘prepared’ for the world that we have in front of us.

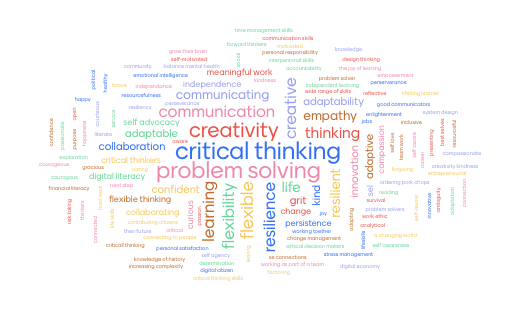

This Friday at noon EST (April 29th, 2022) my students will be presenting the results of their Futures thinking activity. They have been tasked to consider what skills they might need to succeed in the future. They started with the trends that are part of the SSHRC future challenges and built from there. It is capstone presentation at the end of their four month work term in the Office of Open Learning at UWindsor. Join us. We’d love to hear from you.

Why are we doing this?

I do my best to have my student employees do meaningful work. I also try and do the kind of training that might make the experience worthwhile to them. One of the key focuses of that training in the last two years has been the gap between their expectations of what it means to work and what I am actually asking them to do. I have found that I need to spend significant time making students believe that I am actually looking for their ‘opinion’ and not ‘the right answer’. They struggle (at first) confronting things that are uncertain. They want a clear question with a clear answer.

This experience led me to take a closer look at the ‘future preparation of students’ conversation. Whether we are talking about 21st century skills, or preparing people for future jobs or whatever… what are we preparing them for? Is confronting uncertainty a 21st century skill? Are other people in my field seeing the same things from students? What other things should I be trying to prepare them for that haven’t occurred to me that I’ve overlooked? How many of those are the results of my own embodiment and privilege? What, eventually, does this mean we should be doing to change what and how we teach?

I don’t know. I know that I care about the work I’ve done with my students and I believe that there is some kind of disconnect. Over the next ten months I’m going to be hosting a series of conversation to talk about it. I’m planning an open course for the fall. I’m also currently applying for funding for a conference in February of 2023. Stay tuned.

A few thoughts going forward.

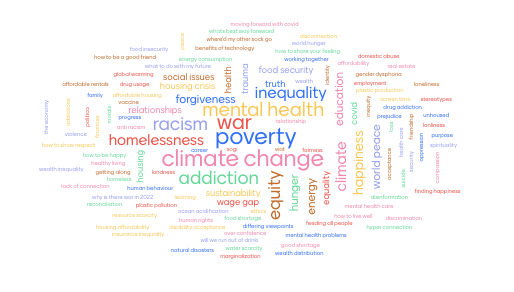

Uncertainty

You might believe that uncertainty is the product of our current times (pandemic, war in Europe, housing and oil prices, climate change etc…). You could see the next 20 years as a time of potentially unprecedented uncertainty. You might also believe that the abundance of access to voices and information have unveiled the uncertainty that has always lain underneath the veneer of the post WWII ‘clear objectives’ global north west. Either way. I feel pretty comfortable suggesting that many of the new challenges our OOL students will be facing in the next 20 years don’t have ‘answers’ and, frankly, the ones we’re handing on (eg. poverty) don’t have ‘answers’ either.

I think that preparing people for uncertainty is different than preparing them for certainty. I was talking about uncertainty a few weeks ago and was told that we need to ‘teach the basics‘ so that people can even enter the conversation. We need to teach the certainties before we teach the uncertainties. I hear it. We were making the same criticisms of whole language learning in the 80s. I just have this feeling that this conversation about uncertainty and what we can do for it is important.

Futures thinking

Futures thinking is a method of examining current trends through the lens of the future. It is NOT prediction. Take your time machine back 5 years and make some guesses… your predictions were probably wrong. If they were right… no one listened to you.

Futures thinking is about creating ‘possible futures’ that give us a chance to discuss our current trends outside of the current disagreements we may have about them. We combine trends and think about what would happen if they became a dominant trend in our culture. What if, 20 years from now, housing prices went up by 500%? What if advances in cyborginess gave us all unlimited mental storage?

The possibilities are endless, but the future is not the thing. The real advantage of taking a futures approach is the chance to think about the trend. The outcome is a better understanding of what we should be doing in our world right now.

What do I hope to get from this?

Well. I have this conversation that I want to be in. I can’t find it… so I’m hoping to start one version of it and find the others that are already ongoing.

I’m also hoping to pull together the wisdom we come across. We’ll see how things develop, how many voices decide to join. It’d be great if that October open course actually became a MOOC. I’d like that. We’ll see.

Interested?

For sure come to the presentation on Friday. For now drop a comment on this post if you’re interested. I haven’t quite settled on the platform for communications (what with the recent unpleasantness in the social mediasphere).