I did another presentation on campus yesterday talking about what it means that students can now generate answers to assignment questions. I often find that writing out some concepts before a presentation helps me focus on what might be important. My pre-writing turned into a bit of a collection of the things that I’ve been pulling together for my session next week on adapting your syllabus.

I’m going to keep working on it, but I figured I would post it on my lonely blog, just to let it know that I still love it.

Introduction

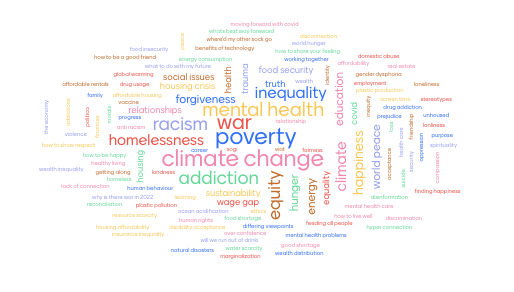

The release of ChatGPT on the 30th of November, 2022 has brought into focus a change that has been coming to higher education since the advent of the Internet. Our students have increasing access to people and services on the Internet that provide them with ways to circumvent the intent of many of the assessments that have been traditionally used in higher education.

Schinske and Tanner (2014) describe four purposes for assessments: feedback, motivation, student ranking and the objective evaluation of knowledge. Regardless of what combination of these purposes you use in your work, or what others you might add, the internet has changed the education landscape through,

- The availability of connection to other people to support our learners with assessments. (by text-message, online chat etc…)

- The availability of pre-created content (available through search or on sites like Chegg) that can be used to respond to our existing assessments

- The availability of generative systems (AI systems like ChatGPT) that can create responses to assessments

This has the potential to impact the effectiveness of our assessments. This is particularly problematic where our assessments are meant as motivation for students to learn. With the plethora of options for students to circumvent the intent of our assessments this require the rethinking of the way we design our courses.

This document takes a neutral position with regards to the student decision to use these connections and tools. These tools exist and the tracking tools that have been designed to identify students who have used these tools are resource heavy, time consuming to use effectively, ethically suspect and ultimately unreliable. We believe that a combination of good strategy in our assessment choices, a focus on student engagement in our classrooms and the establishment of trust relationships with students will be the most effective way forward.

Considering the purpose of assessments

The assessments we provide in our courses each serve a purpose. It can be helpful at the start of the process of reconsidering your assessments to chart what purposes each of your current assessments serve. The following model is developed from Schinske and Tanner article.

| Description of assessments | Feedback on performance | Motivator for student effort | Scaling of students | Objective knowledge |

In completing this chart, it is likely that many assessments will fall into several categories. The new tools will impact the reliability of each of these purposes, but some more than others. The biggest impact will probably be in the motivation section.

This kind of course redesign is also an excellent time to consider overall equity in your course (see Kansman, et. al. 2020).

Grades as feedback on student performance

In this view grades are given to students in order to let them know how they are performing in our classes. The evaluative feedback (grades) give them a quantitative sense of how they are doing based on your measurement of performance. The descriptive feedback (comments) is the feedback that you provide students in addition to that grade in order to explain how they can improve their performance or indicate places of particular strength.

Questions to ask:

- Does my approach provide an opportunity for students to improve on their performance in a way that would encourage them to return to their own work and improve upon it?

- Do the affordances of existing content websites and AI generation programs impede my ability to provide feedback on the performance of students to help them improve given my current assessment design?

Grades as motivator of student effort

“If I don’t grade it they won’t do it”. Whether you consider it a threat or encouragement, this is the idea that we create assessments in order to encourage students to ‘do the work’. This could be encouraging students to do the actual work that we want them to do (eg. assess a piece of writing a student has done to encourage effective writing) or indirectly (eg. assess a response to a reading to encourage the student to do the reading).

Grant and Green tell us that extrinsic motivators like grades are more effective at encouraging logarithmic or repetitive tasks, but less effective at encouraging heuristic tasks, like creativity or concentration. (2013) Content and AI systems are excellent at supporting students to do logarithmic tasks without the need to learn anything.

Questions to ask:

- Does my grading motivate students to learn (as opposed to simply complete the task)?

- Is the learning they are doing the learning that I intend?

- Do the affordances of existing content websites and AI generation programs impact the motivation of students to learn in response to my assessment motivator?

Scaling – Grades as tools for comparing students

This is about using grades to create a ranking of students in a given class. There is a great deal of historical precedent for this (Smallwood, 1935), but it is not clear that this is necessary in the modern university. One way or the other, the curving does depend on the validity of the assessments.

- Is grading on a curve mandatory in my program?

- Do the affordances of existing content websites and AI generation programs accurately reflect the different performances of students?

Grades as an objective evaluation of student knowledge

Using grades to objectively reflect the knowledge that a student has on a particular subject. There will doubtlessly be differing opinions on whether this is possible or even desirable, but, similarly to the scaling conversation, this is subject to the validity of the assessments.

- Do my grades provide reliable information about student learning?

- Do the affordances of existing content websites and AI generation programs allow me to accurately measure objective students knowledge given my current assessment design?

- Is the same objective knowledge necessary for students to memorise in the same way given these new technologies?

Ideas for adapting the syllabus

Teach less

Reducing the amount of content that you are covering in a course can be a great way to focus on critical issues. It also gives students a chance to dig deeper into the material. This opens up new opportunities for assessment.

- Iterative assignments – if students are focused on one or a few major themes/projects you can assign work that builds on a previous submission. Process writing is a good example of this. The student submits a pitch for a piece of writing for an assessment. Then the student continues with the same piece of work to improve it based on feedback given to them by the professor.

- Have students give feedback on each other’s project – When assignments start and end in a week, the feedback that a student gives to another student does not always get reviewed or have a purpose. If students are required to continuously improve their work, this could increase the investment that students have in investing in their work. This approach is, of course, subject to all of the challenges involved in peer assessment.

Lower the stakes for assessment

High stakes or very difficult assessments (20% or more in a given assessment) makes the usage of content or AI systems more valuable in the cost/benefit analysis for students. Lowering the stakes (regular 10% assessments or lower) could reduce student stress levels and encourage students to do their own work. This does, however, run the risk of turning assessments into busy work. It’s a balance.

Consider total work hours

Review your syllabus and consider how many hours it would take a student to be successful in your course. Consider the time it would take a non-expert to read the material for understanding, the time to do research and the time to complete assignments in addition to time spent in class. Would an average student at your school have time to complete the assessments they’ve been assigned given the total amount of work they need to do in all their classes?

Do more assessed work in class

Doing the assessment in class can be an easy way to ensure that students are at least starting the work themselves. More importantly, it gives students a chance to ask those first questions that can make the work easier for them to engage with.

Reduce the length of assignments

Based on the Total Work Hours conversation above, consider whether the length of your assignments improve upon the intent of the assessment. Does a longer essay give them more of a chance to prove their knowledge or does it fairly reflect their performance? Is it possible that the longer assignments only support students who have more disposable time to complete their assignments?

Change the format of the submission

Not all work needs to be submitted in academic writing form. If you’re looking for students to consider a few points from a reading or from conversations in class, encourage them to submit something in point form. Changing the format of the submission can provide some flexibility for the students and also make the work more interesting to grade.

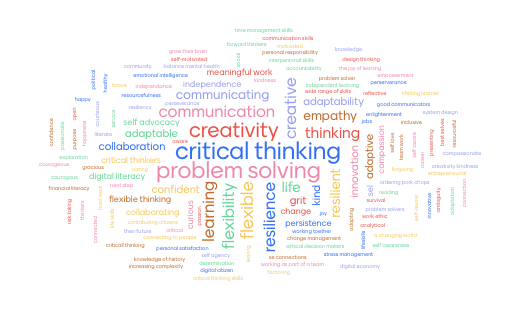

Ill-Structured (ill-defined) problems

A well structured problem is one where the question, the approach to solving the problem and the solution are all known to the problem setter (or, at least, are knowable). An ill-structured problem is one where one, two or all of those are not-known or not-knowable. Well-structured problems encourage students to search for the ‘right answer’. Ill-structured problems require a student to make decisions and apply their own opinion. (see Spiro et. al., 1991)

Rhizomatic Learning/Heutagogy

Approaches to learning where the curriculum in a given course is developed in partnership with students. Often called self-directed learning, these approaches aim to develop a learner’s ability to find, evaluate and incorporate knowledge available thereby developing essential skills for working in a knowledge landscape of information abundance. (see Cormier 2008 & Blaschke 2012)

Effort-based grading

While sometimes controversial, the move to an effort based grading approach has been shown as effective at encouraging students to take risks and be more engaged in performing their assignments while still helping students develop domain specific knowledge (Swinton, 2010). In this model students aren’t being judged on getting work ‘correct’ but rather their willingness to engage with the material. This can be done with a rubric, or by making assignments pass/fail.

Ungrading

This refers to finding new ways to motivate students to participate in the work without using grades. Even advanced students struggle with this approach without specific guidance on how this can be done (Koehler & Meech, 2022) so this requires a significant shift in the approach to designing a course.

Contract Grading

A highly interactive approach to designing a course that gives students the choice of what assignments they wish to work on and, in some cases, allows students to decide on the amount of work they choose to do for the course. This approach, when done for an entire course, can potentially conflict with university and departmental guidelines and you might want to discuss it with colleagues. It might be easier to begin this approach as a section of a course rather than for an entire course. See Davidson, 2020.

Assignment integration across courses

Another approach, which does require coordination between different faculty members, is to have assignments apply to more than one course. It could be as simple as an academic writing course supporting the essay writing in another course or full integration in a program where a given project grows throughout a student’s experience moving through a program.

References

Blaschke, L. M. (2012). Heutagogy and lifelong learning: A review of heutagogical practice and self-determined learning. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 13(1), 56–71. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v13i1.1076

Cormier, D., How much ‘work’ should my online course be for me and my students? – Dave’s Educational Blog. (2020, June 20). https://davecormier.com/edblog/2020/06/20/how-much-work-should-my-online-course-be-for-me-and-my-students/

Cormier, D. (2008). Rhizomatic education: Community as curriculum. Innovate: Journal of Online Education, 4(5), 2.

Davidson, C. (2020). Contract Grading and Peer Review. https://pressbooks.howardcc.edu/ungrading/chapter/contract-grading-and-peer-review/

Grant, D., & Green, W. B. (2013). Grades as incentives. Empirical Economics, 44(3), 1563–1592. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-012-0578-0

Kansman, J., et. al. (2020) Intentionally Addressing Equity in the Classroom | NSTA. (n.d.). Retrieved April 20, 2023, from https://www.nsta.org/journal-college-science-teaching/journal-college-science-teaching-novemberdecember-2022-1

Koehler, A. A., & Meech, S. (2022). Ungrading Learner Participation in a Student-Centered Learning Experience. TechTrends, 66(1), 78–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-021-00682-w

Radzilowicz, J. G., & Colvin, M. B. (n.d.). Reducing Course Content Without Compromising Quality.

Schinske, J., & Tanner, K. (2014). Teaching More by Grading Less (or Differently). CBE Life Sciences Education, 13(2), 159–166. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.CBE-14-03-0054

Smallwood, M. L. (1935). An historical study of examinations and grading systems in early American universities a critical study of the original records of Harvard, William and Mary, Yale, Mount Holyoke, and Michigan from their founding to 1900,. Harvard University Press. http://books.google.com/books?id=OMgjAAAAMAAJ

Spiro, R. J., Feltovich, P. J., Feltovich, P. L., Jacobson, M. J., & Coulson, R. L. (1991). Cognitive Flexibility, Constructivism, and Hypertext: Random Access Instruction for Advanced Knowledge Acquisition in Ill-Structured Domains. Educational Technology, 31(5), 24–33. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44427517

Swinton, O. H. (2010). The effect of effort grading on learning. Economics of Education Review, 29(6), 1176–1182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2010.06.014

Trail-Constant, T. (2019). LOWERING THE STAKES: TIPS TO ENCOURAGE STUDENT MASTERY AND DETER CHEATING. FDLA Journal, 4(1). https://nsuworks.nova.edu/fdla-journal/vol4/iss1/11