I’m into Year Two (of two) leading digital strategy for the K-12 system here in PEI. I landed in a wonderful situation where almost all the hardware (computers and wires) system-wide had just been replaced when I arrived, and where the educators and curriculum/governance people involved are interested in having conversations about a way forward. But we want a way forward for everyone. How do we make a plan that is inclusive, that develops web literacy and helps support our learners becoming good digital citizens? I’ve become really interested in trying to build some key strategies into the process to help everyone succeed. This is where that thinking is at now.

Where we are in the digital strategy

Year One was mostly about setting the stage for change.

- We’ve built a system wide committee with decision making responsibilities (more on this in another post)

- We’ve built a platform to house curriculum and resources for each course

- We’ve developed a two course approach to building literacy (my own digital practices course and Google Certified Educator)

- We’ve identified and started working on a massive list of things that need attention

- We’re working on grants and partnerships to bring cool stuff (and training) to the system

The targets we’re looking to address

Digital citizenship

This one is first because it’s the most important. We need to understand what literacies we need to be good members of our society in a world that has the internet in it. The internet can give us access to wonderful things, and it also contains piles of people who are purposely trying to mislead us so they can make money off of ads. The internet has entertainment for us and also has terrifying Peppa Pig videos. I would love to be part of a society where each individual is trying to make good choices based on their values and not on fears stoked by some kid in Veles.

Equity

For so many reasons. Once we start talking about technology, the idea of gender equality inevitably comes up. And it should. Our numbers around tech and girls are still not great and there is still way more work to be done. But there are lots of other issues in here as well. Technology (as its often taught) favours the autodidact. It also favours people who have certain kinds of support at home, whether it be access to tech or the habits that are privileged by our education system. I have seen countless folks over the years, big and small, who come to this work with a great deal of fear. I like to think that I have helped some of them succeed through that, but how do you plan that for a system?

Silicon Valley Narrative

I could call this a lot of different things, but lets just say that it’s the ‘we all need to be coders because coding is the future’ argument. The idea that the purpose of this technology is somehow that we are all going to make millions or have nice cushy jobs pushing the world through its fourth revolution. Go and read Hack Education. It’s amazing and will cover these issues way better than I can. Suffice it to say there are more reasons to work on internet things than coding. Coding isn’t bad… it’s just not some panacea that will save the children.

Technology is hard

Well… it is. I have no interest in taking something like an Arduino, or blogging or web literacy and breaking it into tiny bits that will slowly combine over 13 years in our education system. I want each interaction with this stuff to be meaningful, so that means it’s going to be hard to do. I’m not terribly worried about that. Kids are actually quite smart if you let them be. But it’s important always to remember that this stuff can be difficult technically, socially and emotionally.

Project management and socio-emotional support – a partnership

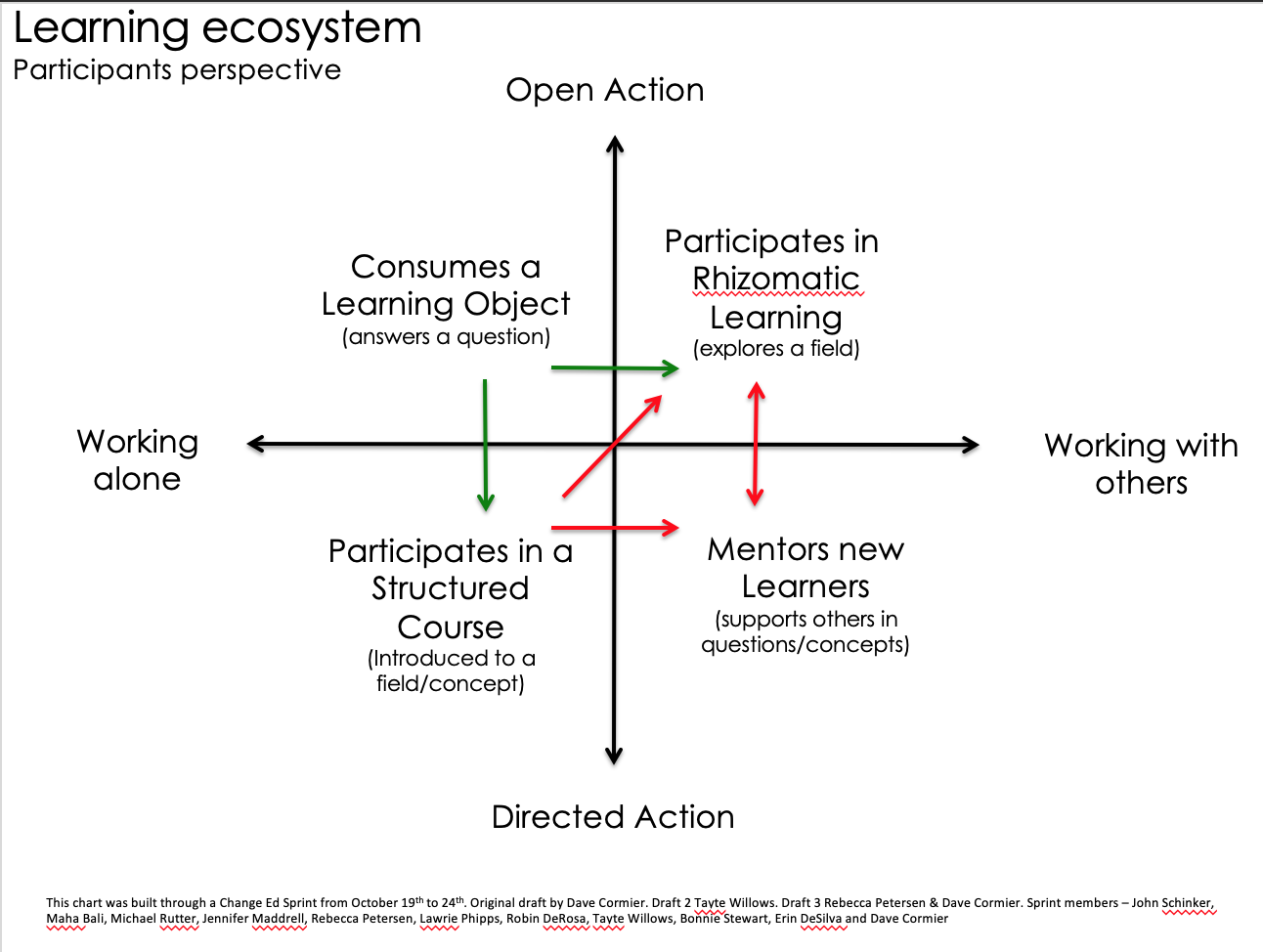

My solution to address this has developed over 15 years. Much of it comes from my experience working with the concepts around rhizomatic learning and watching people struggle to come-to-know using the rhizomatic approach. My approach is based in hundreds of conversations with educators, research I did for Academic Planning at UPEI two years ago, researchy stuff and lots of time spent staring out the window.

Project Management

Nothing has had a bigger impact of my professional career than learning how manage a project properly. I certainly wouldn’t claim that I have fully reached that goal, but it’s something I’m working on constantly. I’ve learned to ask questions like: What is the real goal we’re working on? What change are we trying to make in the world? What objectives will tell me that I’m getting there? What strategies will I use? Who will do the actions? When?

I’d like to see these concepts applied constantly to our work around tech. We do…kinda. What I’m hoping to encourage (I don’t write the curriculum, I’m working with the people who do) is that we standardize the language around project management and the literacies required. We can use it with 7 year old and with 17 year olds. Imagine a school system graduating people that could directly go into the workforce with strong project management skills. Forget about the workforce. Just imagine how much easier it would be for them to plan a weekend party.

Some people seem to come out of the womb with these skills. I am one of the legion that did not.

Socio-emotional support

I’ve waffled on what to call this. I started out by calling it resilience… but I’m finding that I don’t like the connotations sometimes attached to this. Resilience also, to me, suggests that growth as a human is somehow just about sucking it up and trying harder. That’s not what I mean here. I’m talking more about that reflection that allows you to process your feelings when you’re working. The pressure of idea generation. The frustration when something doesn’t work. That feeling you’re falling behind. What do we do about those things? Is it really about just trying harder?

I’ve been walking around with an Arduino kit in my backpack and doing a little test with it. I’ve been putting it in front of people, opening it up and asking them how it makes them feel. Some people say they are really excited by it. Most are not. The majority of the response I get sits somewhere between revulsion and fear. That kind of response doesn’t encourage learning.

How do we build supports to work and talk our way through those feelings, as learners of whatever age? How do we encourage the kind of reflection that allows people to ‘succeed’ AND feel supported and good about themselves in the process?

Putting them together

I think both approaches get stronger when you think of them as a team. Some learners will certainly favour one approach over the other – but I’m fine with that. Structured conversations about what your goal looks like and how to create a timeline are going to keep people on task and give them success milestones. Reflecting on your feelings in that process – “What did you do when you felt like you were lost in the process?” “How did you deal with having too many ideas (or none)?” and, eventually, “How did your idea generation impact your project charter? Did you have to change your timelines?” is important too.

I would love to see us focus our assessment on these two things. I don’t particularly care if your tech project is perfect, or all the lights blink or whatever… what I care about is how much you’ve grown through that process. Did you develop your search literacies when you got stuck? Did you hit your timelines? Did your goal change as you learned more about the process?

I’m not 100% convinced that this needs to stop at digital. I can totally see it applied in the exact same way to a science project or an essay. Imagine if we focused all the project work we work around those two pieces? If we all used the same language, and pulled together towards preparing our kids to have healthy approaches to running projects?

Wish me luck 🙂