It’s been an exciting couple of weeks here in PEI. We’ve launched the first part of the training and discussion for our maker cart project. We’ve been working on pulling together all our information pieces on supporting technology in the system. We spoke with the principals about our work and have had a fair number of them reach out excited to get involved. We’ve been thinking about how technology can support language arts. We’ve been working towards better basic training in technology in the form of google certified educator. We’ve been thinking about how we can improve our wireless infrastructure in the long term. The digital strategy committee approach (yup, I suggested we solve a problem with a committee) has been fantastic. As always… getting the decision making worked out is a critical step in the process, many thanks to the leadership in k12 here for letting us set it up.

Digital Practices

Dedicated time-for-learning is critical for digital transformation (or, really, any change project). While we are planning learning events with teachers for both the maker work and with google, getting time-for-learning with the curriculum consultants and the coaches is just as important. This week we start a 2 month-ish course on digital practices. The course itself is based on the ed366 course I taught at UPEI for years, but modified for smaller class sizes and the more specific use case of being within an education system.

‘Digital Practices’ are the things that I do that are born out of the affordances of our digital communications platforms. It is an assemblage of the digital skills i might have mediated through the digital literacy and habits that i have acquired. Or, to put it more simply, it’s ‘being digital’.

It’s tricky business, talking about this stuff, and it inevitably leads to some contradictions. One of the biggest advantages of digital spaces, from my perspective, is the return to orality. When we depend on a finished text (say, a printed book) to arrive to us in the mail, we are the receivers of the knowledge that is contained therein. I can certainly work through that text with my other, previous learnings, but I never get a chance to contribute, to ask questions that can get answers… I’m not part of the knowledge creation process. When we think of an oral discussion (at least, a good one) there is a chance for both sides to contribute, a chance for us to move together to a new understanding. Digital spaces allow for this to happen with text. We can collaborate on something that becomes knowledge through our interactions with it.

It’s not all sunshine and roses of course. Collaborative texts tend to reduce themselves to consensus… which can be nice, but can sometimes privilege existing ideas over new ones. There is much greater safety in sending out a printed text that people read when you’re not in the room. If the reader hates it, or it makes them angry, you are not in the immediate line of fire. These advantages and disadvantages need new social norms… new practices to make them effective and still maintain our own healthy relationships. These digital practices need to be negotiated, they need to be talked about out loud in ways that many of our 20th century practices don’t. I’m going to run a course about this. It’s going to be fun. A few opening thoughts…

Tools vs. practices

Years of teaching courses like this have lead me to believe that most people are coming expecting to learn ‘how to use a bunch of tools’. I can totally understand this. You see people using tools, they claim to be effective with them, you too want to use the tools. Truth be told the ‘how’ of these tools has simplified (in most cases) to the point where the technical using of them is an almost incidental part of the learning process. There’s all the world of difference between ‘learning how to use a hashtag’ and ‘knowing how to use a hashtag to avoid getting it hijacked’. One involves knowing that when you put a character (#) in front of a word it becomes a tag, and the other involves hours of working in an environment to come to understand how twitter spam/trolls work. People will probably learn how to use tools in the course, but I probably wont be teaching much of it.

Complexity

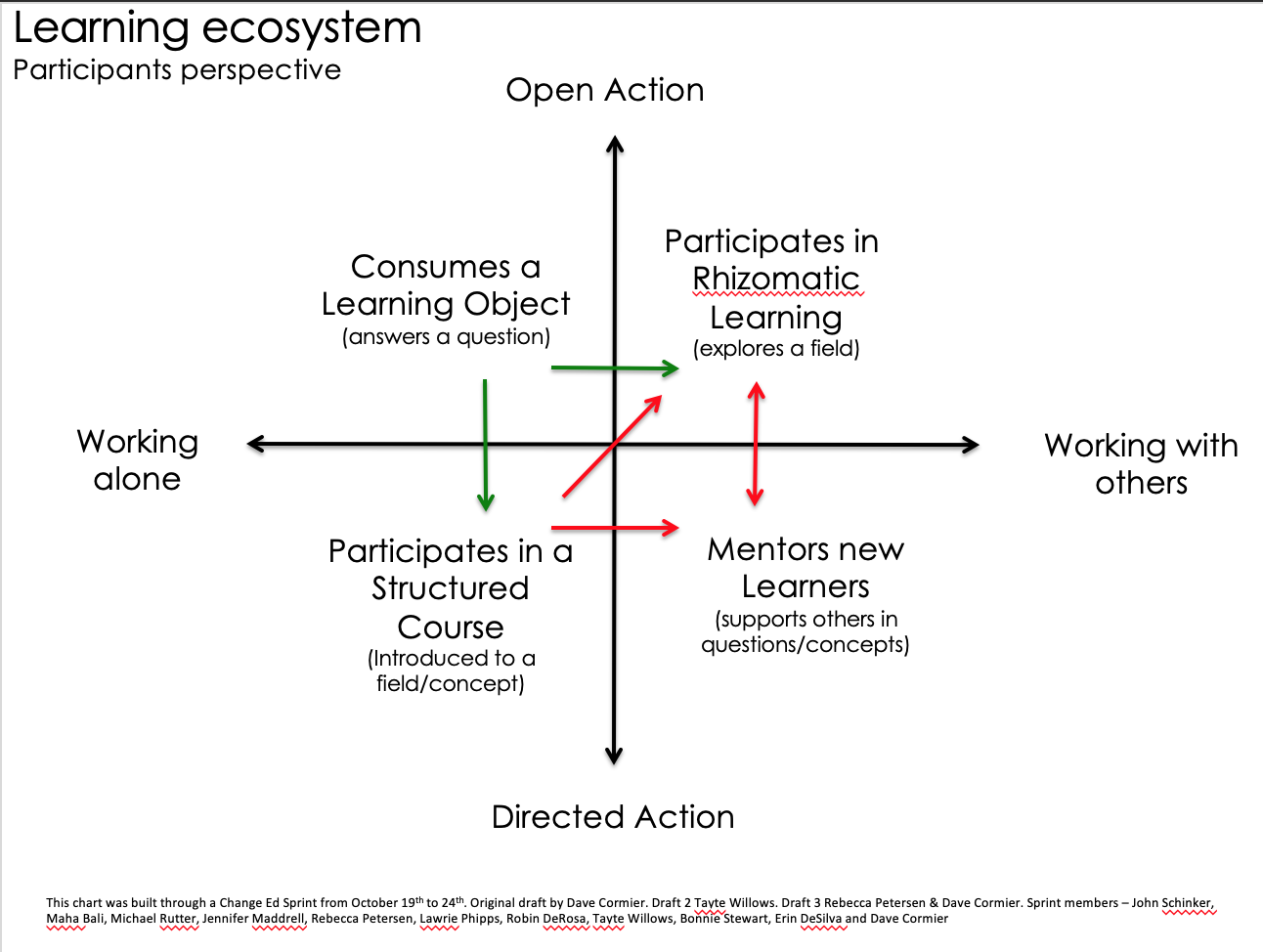

I’m still pretty stuck on the idea of complexity being important when teaching digitally mitigated practice. I think that separating things to learn out into simple, complicated and complex concepts allows us to make space between things that are easily accomplished by more rote means and those that require us to settle into a concept and work our way around inside of it.

Maker

There’s always been a maker strand in my work, but I’ve never formally acknowledged it. I was uncomfortable with the term, but the last six months preparing a maker project here in PEI has led me to feel much better about it. I’m expecting to have a big solid maker section in this course and to use it to demonstrate differing analogue/digital approaches to learning/teaching with it. Do I need to have ideas for the kids before I arrive? How do I structure student lead ideation so that all my students can succeed and I don’t make it teacher centric? Is the internet really full of good ideas? How can I work with other teachers to create more relevant ideation spaces?

Community as Curriculum

It always come back to this for me. I feel more strongly about it now then when i first wrote it 10 years ago. The goal for me is for each person in this course to be able to be able to become a member of a conversation in a community of knowing in the subject. Can you pass? Can you engage? Do you know how to ask questions? Do you speak the language? Can you help? We learn to become members in a community of knowing by practicing and learning together. When the community is the curriculum.

Citizenship

At the end of the day practices lead to citizenship, as they do in the rest of our lives. The ways in which we interact with each other, with our community, our schools ourselves… these all make up our actions as citizens. As more and more of our communications are mediated through the internet, more and more of our lives as citizens are mediated through it as well. If our schools prepare citizens, it is essential that they prepare them for being good citizens, online or offline.