This discussion paper was originally posted in the “International Journal for Innovation and Quality in Learning” which is now not on the internet. With the “learning resilience” Open course starting up in a few weeks (you can sign up at that link if you like), I thought it might be interesting to repost this and see how it sounds 2 years later.

Key message

By creating an event like a MOOC we are potentially radically redefining what it means to be an educator. We are very much at the beginning stages of our learning how to create the space required for community to develop and grow in an open course. These field notes speak to the my own journey in the design of ‘Rhizomatic Learning – the community is the curriculum’. They are, in effect, a journey towards planned obsolescence.

KEYWORDS: rhizo14, rhizomatic learning, MOOC,

Oscar is my almost-eight year old son. He’s been blogging since he was four, has played around a little on twitter and has generally grown up in a house where his parents have made a fair chunk of their career out of blogging and working online. It is with this as a backdrop that he walks into the room yesterday and asks

Are you in charge of ALL of rhizo14, i mean, all around the world?

You see I received a box in the mail yesterday that had a card, 4 t-shirts and a magnet that said #rhizo14 on it. The artwork, the hashtag and the tagline “A communal network of knowmads” come from a Open Course that I started in January of 2014 now called #rhizo14. The package Oscar was looking over had a stamp from Brazil on it which I explained came from Clarissa, an educator who participated in Rhizo14. She sent everyone in the family a t-shirt with the rhizo14 logo on it.

Rhizo14

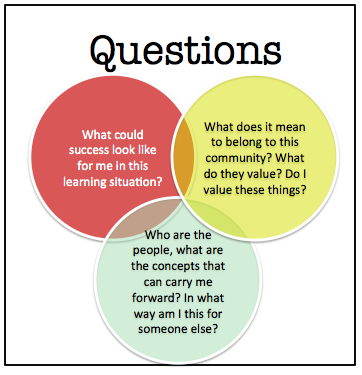

So… are you in charge of it? My son not being accustomed to me being lost for words, was confused by my lack of response. In that simple question lies much of what I have struggled to explain about the event that is/was #rhizo14. What does it mean to be ‘in charge’ of a MOOC? What was my role in something that was very much a participant driven process?

If I am ‘in charge’ what does that mean in terms of my responsibility towards the quality of the experience people have as part of rhizo14?

What was the course now called Rhizo14

I say “now called” because the original title of the course was “Rhizomatic Learning – The community is the curriculum” but the people who are still participating refer to it by the hashtag. It was a six week open course hosted on the P2PU platform from January 14 to February 25th. The topic of the course was to be about my years long blabbing about rhizomatic learning. I wanted to invite a bunch of people to a conversation about my work to see if they could help me make it better. Somewhere in the vicinity of 500 people either signed up or joined one of the community groups.

What I was hoping for

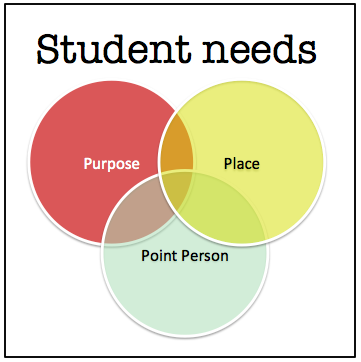

Fundamentally i was hoping that 40 or 50 people would show up to the course and that by the end there would still be a handful of people interested in the discussion. I thought it would be a good opportunity for me to gather the work that I had done and make it better than it was before. I find the pressure of having an audience is very helpful in convincing me to get things together. I was not precisely hoping that we would get enough people for the course to have MOOC like characteristics, and I certainly didn’t put the time into advertising it in a way that was likely to lead to that. I was hoping that after 6 weeks I would have a better grasp on my own work, and that a few participants would have had a good quality experience.

In the more macro sense, I’m always hoping that a course that I’m working on leads to some sort of community. My work since 2005 has focused on ways to encourage people to see ‘the community as the curriculum’. I’m always hoping to organize an ecosystem where people form affinity connections in such a way that when the course ends, and I walk away, the conversations and the learning continues. I think of this as one of the true measurements of quality in any learning experience – does it continue.

How the course was designed

I made three different attempts at designing rhizo14.

The first was around my own collection of blog posts about rhizomatic learning. This was, essentially, the content of 7 years of thinking about the rhizome in education, broken into six week. In retrospect, it seems difficult to believe that I was considering so instructivist an approach, but it is very much following previous models of open courses I have been involved with. I think that this course design was prompted by my concern that people would be unfamiliar with the use of the rhizome in education and would need structure to support their journey with the idea. If you have content to present, you can ensure a certain minimum quality experience. It was also easy to just use the stuff I already had :).

Two days later, I had almost completely discarded this model for a new one that was more focused on the process of learning and connecting in an open course. The idea in model two was to ‘unravel’ the course from a fairly structured beginning to a more open and project based conclusion. This design was meant address my concerns about new participants to open/online courses. Over the years we’ve seen many complaints about the shock of a distributed course and, I’ve always thought, we didn’t see the vast majority of the complaints of participants who just couldn’t get their feet under them and didn’t complain publicly. Here I was trying to ensure quality from a process perspective.

Two days before the course started, I threw that out the window as well. In discussions with the excellent Vanessa Gennarelli from P2PU she suggested that I focus the course around challenging questions. It occurred to me that if i took my content and my finely crafted ‘unravelling’ out of the way I might just get the kind of engagement that could encourage the formation of community. The topic I chose for week 1 mirrored the opening content i was going to suggest but with no readings offered. I gave the participants “Cheating as Learning” as a topic, a challenge to see the concept of cheating as a way of deconstructing learning, and a five minute introductory video. This is the format that I kept for the rest of the course, choosing the weekly topics based on what I thought would forward the conversation. Here the quality of the experience is left up to the participant to control.

■ Week 1 – Cheating as Learning (Jan 14-21)

■ Week 2 – Enforcing Independence (Jan 21-28)

■ Week 3 – Embracing Uncertainty (Jan 28-Feb 4)

■ Week 4 – Is Books Making Us Stupid? (Feb 4-Feb 11)

■ Week 5 – Community As Curriculum (Feb 11-Feb 18)

■ Week 6 – Planned Obsolescence (Feb 18-?)

What happened during the course

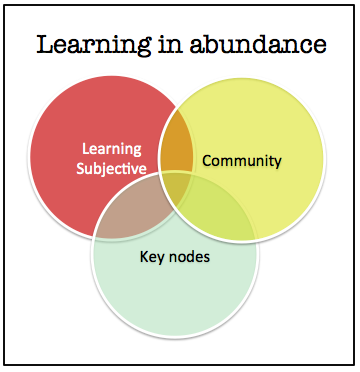

Saying that I lost control of the discussion creates the false premise that I ever had control of it. From the get go, participants took my vague ‘cheating’ prompt and interpreted it in a dozen different ways. There were several strands of ethical debates regarding cheating. There were folks who decided to discuss testing. Others focused on how learning could be defined in a world of abundance. Still more took issue with the design of the question and focused on this. There was a varying degree of depth in these discussions, and, frankly, a certain amount of debate on what qualified as valid discussion.

My response was to (as i had promised) write a blog post explaining my intention with the question and surveying what people had written. This was the only week that I did this. As the course developed, and new challenges emerged, it became clear that these review posts were being created without my help. They were, in essence, me trying to hold on to my position as the instructor of the course. A position I had not really had from day 1. By the end, I only formally participated as instructor in posting the weekly challenges with a short video and by hosting a weekly live discussion on unhangout. The community has become its own rhizome, in the sense that it had created space for multiple viewpoints to coexist at varying levels of discussion.

What happened after the course

My ‘planned’ course finished on the 25th of February. On the 26th of February, week 7 of the course showed up on the Facebook group and the P2PU course page. This week entitled “The lunatics are taking over the asylum” was the first of many weeks created by the former ‘participants’ in the course. This new thing, which it is now safe to call #rhizo14, is currently in week 11 of its existence. In week eight, the community chose a blog post that I wrote several years ago as a topic of discussion. Week 11 is addressing the concern of allowing all voices to be acknowledge (a discussion that was very much present during the first six weeks) in an open environment.

As they began so they continued. The vast majority of the people who participated are now only distantly connected to the course if at all. A core of 50 or so people remain in the discussions, however, and are now identify themselves as ‘part of rhizo14′. For now, at least, there is a community of people who I am happy to number myself a member of. When I consider my responsibility as a ‘leader’ in this sort of community, it makes me wonder whether ‘educator’ is even the right word for it.

So Oscar… am I in charge of Rhizo14

Uh… no. I don’t think I ever was. An amazing group of people from around the world decided to spend some of their time learning with me for six weeks. A fair number of those seem to be forming into a community of learners that are planning new work and sharing important parts of their lives with each other. We are creating together. And it can’t be up to me to decide what good means for any of them.

My son, by this point of the conversation, would doubtlessly already be asleep.